|

|

|||||

Sinixt |

|

|||||

|

The Sinixt, known also as the Arrow Lakes Indian Band, are the First Peoples of the Upper Columbia Basin, a watershed area that spans British Columbia (BC) and Washington State. "When the first European explorers arrived in this area, they encountered a rich culture that had flourished in this region for many thousands of years. Despite an apparent genocide perpetrated against the Sinixt, and having been declared officially extinct by the Canadian government, descendants of the Arrow Lakes Peoples continue to maintain a presence locally" Sinixt Nation.

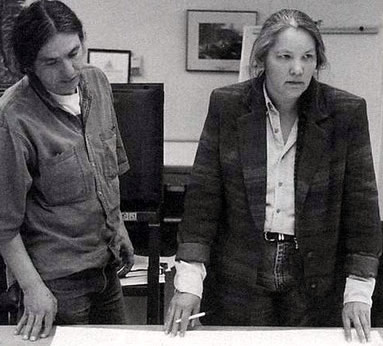

Sinixt Robert Watt and Marilyn James, 1999. |

Sinixt Traditional Territory. (Click to enlarge) The "Lakes" indigenous people were given their name because their territory was centered on the waterways of the Arrow Lakes region. Today Robert Watt and Marilyn James (left) accept their moral obligation as Sinixt to care for their ancestral land and traditional burial sites. Listen to their documentary: Keeping the Lakes Way. |

|||||

|

In 1972 Charlie Quintasket (right) from the Colville Indian Reservation in Washington State began to investigate why his Lakes people had no Indian Reserves in Canada. As a Sinixt speaker, Quintasket and a number of other Lakes and Colville elders participated in the BC Indian Languages Project initiated by Randy Bouchard and Dorothy Kennedy. Their comprehensive ethnographic, ethnohistoric and linguistic research on the Lakes people is compiled in First Nations' Ethnography and Ethnohistory in BC's Lower Kootenay Columbia Hydropower Region (2000, 2005). Other references include: Cliff Woffenden; Ghost Peoples; Celia Gunn, A Twist in Coyote's Tale (2006): Eileen Delehanty Pearkes: The Geography of Memory (2002); Paula Pryce: 'Keeping the Lakes' Way.' Reburial and the Re-creation of a Moral World among an Invisible People (1999). See also the website by the Sinixt Nation Society: www.sinixt.org. |

Sinixt elder Charlie Quintasket. |

|||||

Bull Trout of the Upper Columbia, Sinixt Territory. |

The Sinixt speak a dialect of the Okanagan - Colville language in which "Sinixt" (sngaytskstx) translates as "Place of the Bull Trout." Like the Sinixt, the Bull Trout (Salvelinus confluentus) is an ancient resident of the upper Columbia Basin. Today the Bull Frog is on the edge of extinction due to industrial forestry and other forms of development that have destroyed its habitat. "Sinixt descendants believe that their ancestors were victim to deliberate smallpox infestations. Such epidemics were common throughout the Americas in the first few centuries of European migration, a time described as the Great Dying. As they were the Mother Tribe, it is speculated that the government and economic powers of the time targeted the Sinixt in order to diminish resistance from other tribal groups" Sinixt Nation. |

|||||

Government plaque, 1954. (Click to enlarge) |

In 1954 the BC government marked the anniversary of the International Boundary in Sinixt Territory. The so-called Indian Legend Plaque (left) commemorates the event that led to the annihilation of the Sinixt: "When the International Boundary line was being surveyed in 1857-1861, the major portion of the large Indian band then living in this area moved to the reservation at Colville, Washington. One of the Indians entwined two sapling pines, saying 'Though Divided We Are United Still - We Are One.' This tree symbolizes the spirit of friendship existing between Canada and the United States." In 1956 Canada declared the Sinixt officially extinct, a decision that left those Sinixt members living on the Colville Reservation or scattered among other ethnic groups in BC without recognition under the Indian Act. |

|||||

"Chief Edward," Sinixt Chief, 1872. |

Mattie, daughter of Chief Edward, c. 1950. Chief Edward (left) was one of the last hereditary Sinixt chiefs. His daughter, Mattie (above), lived until the mid 20th century. By this time, most Sinixt had officially "vanished" from their territory in the West Kootenay. Having sustainably managed their homeland for many thousands of years, the only traces the Sinixt left behind of their presence in the landscape were archaeological. "From the headwaters of the Columbia River north of Nakusp, to Kaslo in the West, Revelstoke in the East, and down into what is now known as Washington State, the Sinixt people lived in harmony with this land. They had extensive trade routes known as grease trails, traveled by foot and with sturgeon nosed canoes, lived in pit houses, hunted caribou, fished and gathered wild plants and medicines" Sinixt Nation. |

|||||

|

In his 1825 journal, Scottish botanist David Douglas described an Indian burying ground on his trip to Fort Colville as "one of the most curious spectacles I have seen in the country. . . The body is placed in the grave in a sitting position, with the knees touching the chin and the arms folded across the chest. It is very difficult to get any information on this point, for nothing seems to hurt their [the Indians'] feelings more than even mentioning the name of a departed friend." Decades later a similar scene was depicted by the explorer R. C. Mayne (right) in his 1862 account: Four Years in BC and Vancouver Island. Neighbouring peoples to the Sinixt did not bury their dead in a sitting position, making burial grounds an accurate determinator of territorial boundaries. For the Sinixt, who are asking for recognition and reinstatement, such evidence is vital. Traditional Sinixt burial grounds were located alongside lakes and rivers and it is a great loss that so many have been destroyed by hydro development. |

"Indian Burial Ground." Engraving. (Click to enlarge) |

|||||

Kettle Falls. Painting by Paul Kane, 1848. |

The European invasion of the West Kootenay caused a Sinixt diaspora: whole valleys were depopulated by disease and epidemics and the survivors were dispossessed by miners and settlers. Vast fortunes were made from degrading the earth, poisoning the lakes and clearcutting the ancient forests. Dams killed off the salmon and destroyed Sinixt villages and burial sites. The first recorded contact between the Sinixt and Europeans ocurred in 1811 when British explorer David Thompson paddled up the Arrow Lakes. Later, American and British fur traders travelled up the Columbia River. In 1825 they built Fort Colville close to the site of an important aboriginal fishery and trading centre. Early pictures of "Kettle Falls" and Sinixt were by Paul Kane (left and below). |

|||||

"Kettle Falls, Columbia River." Engraving, c. 1855. Above: another early view of Kettle Falls is an engraving by John Mix Stanley depicts an aboriginal man and woman fishing with a net and basket. Sinixt women were skillful basket makers: using plant materials such as branches, bark, roots and grasses, they wove a variety of baskets for cooking, carrying and storage. For catching salmon, they made basket traps of young Douglas fir poles which were woven together with hemp rope and placed across the Falls. |

Sinixt man, drawing by Paul Kane, c. 1847. |

|||||

Salmon was the richest and most vital wild food source for the indigenous peoples of the Columbia Basin. Every year anadromous runs of coastal salmon — Chinook, Sockeye and Coho — and steelhead trout returned to spawn in the freshwater tributaries of the Columbia River, from its Pacific mouth, to the upper reaches of Sinixt Territory. The Sinixt made annual trips to Kettle Falls to take part in the aboriginal fisheries with their neighbours, the Skoyelpi (Colville). According to traditional customs to distribute the wealth, a Salmon Chief was appointed to ensure that the salmon harvest was shared with everyone in the camp. During his visit to Fort Colville, the artist Paul Kane sketched the Salmon Chief of Kettle Falls, known as See-pays (left). He noted that while the Salmon Chief "had taken as many as 1700 salmon, weighing on average 30 lbs, in the course of one day," he was considerate in leaving enough fish for the Indians on the upper part of the river. In the 1850s, Washington Territory was opened up for settlement following the agreement on the international boundary. Thousands of gold miners came up the Columbia River disrupting aboriginal fisheries at Kettle Falls and elsewhere. The indigenous peoples tried unsuccessfully to stop the invasion from continuing into the Upper Columbia Basin where the rugged inaccessibility of the northern Sinixt Territory provided a safe haven until the late 1880s. |

See-pays. Painting by Paul Kane, 1850. |

|||||

"Kettle' Falls' A Salmon Leap." Engraving. |

The "International Boundary Survey" was carried out from 1857 to 1861. Its mission was to mark the 49th parallel from the West Coast to the Rocky Mountains according to the treaty signed in 1846 between Britain and the United States. This artificial north south division cut the indigenous tribes off from their traditional territories by preventing their seasonal moving to different resources and locations, a lifestyle on which hunter fisher gatherer peoples were dependent. English naturalist John Keast Lord accompanied the "Boundary Survey" and in 1866 published a narrative: The Naturalist in Vancouver Island. An engraving of Kettle Falls does not show the spectacular runs of salmon for which it was most famous (left). Lord wrote: "There was no place in the world" he wrote, "where salmon were as abundant as at Kettle Falls." The naturalist noted how dependent the aboriginal people were on the salmon runs, ominously adding: "were we at war with the Redskins, we need only to cut them off from their salmon fisheries to have them completely at our mercy." |

|||||

By 1855, most Washington tribes had been forced to accept treaties. The seven remaining "hostile" chiefs of the Upper Columbia River were persuaded to surrender in 1856 by a Jesuit missionary. To mark the treaty signing, a photograph was taken of the tribal chiefs with Father De Smet (right). Front row, left to right: Victor, Kalispel tribe; Alexander, Pend Oreille tribe; Adolphe, Flathead tribe; Andrew Seppline, Coeur d'Alene tribe. Rear row: Dennis, Colville tribe, Bonaventure, Coeur d'Alene tribe; Father De Smet; Francis Xavier, Flathead tribe. The so called "Colville Indians" were given a reservation in 1872 which artificially amalgamated five First Nations, including the Sinixt. In 1891 large sections of the northern part of the reserve were revoked for settlement, leaving the Sinixt with none of their traditional territory: Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation. |

Indian Chiefs of the Upper Columbia, c. 1859. |

|||||

Chief Joseph, Colville Indian Reservation, 1903. |

Chief Joseph of the Nez Percé was exiled to the Colville Indian Reservation in 1885 (left). The famous Chief led a courageous retreat from the US military following the forced eviction of the Nez Percé people from their homeland in Wallowa Valley (present day Oregon). On his surrender in 1877, he was first exiled to Oklahoma, and later transfered to Colville with the few survivors of his people. Here he remained a political prisoner until his death in 1904, said to have been caused by a broken heart. Military operations by Americans also had a dramatic effect on the Sinixt, some of whom fought with Chief Joseph. |

|||||

In the 1880s the rapidly expanding immigrant population of the West Kootenay led to the removal of the indigenous peoples from their land, following the same pattern as in the US. The Sinixt were discouraged from making their seasonal trans-border trips south to the Kettle Falls fishery. Chief Kinkanaqua, known as the last Salmon Chief at Kettle Falls, may have been a Sinixt (right). The pervasive lack of understanding of Sinixt identity and territory resulted in lack of official recognition when the Department of Indian Affairs conducted its 1881 census for the Canadian government.

Colville Indians fishing at Kettle Falls, c. 1930. |

Chief Kinkanaqua, the last 'Salmon Chief,' c. 1895. The traditional fishing practices at Kettle Falls continued until 1933, when the construction of the Grand Coulee Dam began. An archival photo shows how dipnetting was carried out (right). Using long poles, aboriginal fishers stood on precarious wooden platforms made from giant logs positioned directly over the turbulent water. |

|||||

"They cut down the Old Pine Tree," 1941. |

Book cover: Grand Coulee Dam. In 1947, the US Bureau of Reclamation published a book (above) subtitled The Eighth Wonder of the World: Grand Coulee Dam. The huge dam was described as a "monument to prosperity" that had been created from a "barren wasteland." There was no mention of the dispossession of the aboriginal inhabitants, the loss of salmon runs, or the destruction of 52,000 acres of old growth forests. In 1941, the cutting down of the last tree was marked by a formal ceremony, before inundation (left). Large areas of the Colville Reservation were flooded by "Lake Roosevelt," which stretched 151 miles north, from the dam to the international border with Canada. |

|||||

Colville women at the Ceremony of Tears

marking the end of the salmon runs at Kettle Falls, Washington, 1939. |

||||||

For the indigenous peoples of the Upper Columbia Basin, the Grand Coulee Dam was a disaster. In 1939, the Colville Indians held a "Ceremony of Tears" (above) to mark not only the end of the salmon fishery at Kettle Falls but a way of life. "Toopa," an Arrow Lakes elder (right) remembered the Kettle Falls before it was covered over by the massive concrete structure: Every summer, my family camped at the Falls. When the salmon swam upstream to spawn, the water became so thick and matted with their red bodies that it looked as if you could walk across the river on the backs of In - Tee - Tee - Huh: The River Lost. "Syniakwateen. (The Crossing)," 1866. |

Toopa, an Arrow Lakes Band Elder. Another traditional Sinixt meeting place was "Syniakwateen" (left), a crossing at the narrowest neck of the Pend d' Oreille River. In his narrative, John Keast Lord wrote: "The scenery is picturesque beyond description, densely wooded on each side, the river winds its way through a series of grassy banks, flat and verdant as English meadows." He described the remarkable Indian canoes designed to traverse the river, which were made of a large sheet of bark that had been "stripped from a spruce fir [sic], tightly sewn at both ends, and shaped to form a conical point" The Naturalist in Vancouver (1866). |

|||||

Scottish botanist David Douglas was the first scientific traveller to visit the Arrow Lakes. In his 1827 journal, he wrote "Not a day passed, but brought something new or interesting either in botany or zoology." He noted how the Indians use the lichen on pine trees to make a "bread cake." "The canoes of the natives here are different in form from any I have seen before," he wrote "The under part is made of the fine bark of Pinus canadensis (Pine) [sic] and about one ft from the gunwale of birch-bark, sewed with the roots of Thuya (Cedar) and the seams neatly gummed with resin from the pine. They are 10 to 14 ft long, terminating at both ends sharply and bent inwards so much at the mouth that a man of middle size has some difficulty in placing himself in them. One that will carry six persons and their provisions may be carried on the shoulder with little trouble." |

"Eventide, Procter, BC," c. 1900. |

|||||

"A Kootenay Indian Pine Bark Canoe," c. 1900. |

Paul Kane was another of the first non natives to paddle up the Arrow Lakes in 1847. A photo by Baillie-Grohman, taken c. 1900, captures Kane's journal description: "The chief, with his wife and daughter, accompanied us in their canoe, which they paddled with great dexterity, from ten to fifteen miles. They make their canoes of pine bark, being the only Indians who use this material for the purpose; their form is also peculiar and very beautiful. These canoes run the rapids with more safety for their size, than any other shape." |

|||||

The elegant bark canoe of the Kootenay was much admired for its lightness in making portages and its stability in navigating rapids (right). The unique design and appearance of the canoe was described as "sturgeon-nosed" similar to the primordial fish which inhabited the local lakes and rivers. Bark canoes were the primary transportation for the Sinixt whose homeland included the watersheds of three major rivers: Pend d'Oreille, Kootenay and Columbia.

Prehistoric white sturgeon, BC. |

Sturgeon nosed canoe, Okanagan Lake. White sturgeon (Acipenser transmontanus) is the largest freshwater fish in North America. Historically, it inhabited the Columbia River from the Pacific mouth to far upstream into Canada. A commercial sturgeon fishery began in the 1880's at Kettle Falls but by 1899 it had collapsed. Sturgeon are long lived and slow growing fish which can become 100 years old. Females do not spawn until 18 years of age, making recovery of the species difficult. The government's belated effort to halt the extinction of the species has had little effect: Environmental Stewartship Division. |

|||||

Sinixt encampment, West Kootenay, c. 1900. Archival photos of Sinixt people are rare. A photo of an encampment on a West Kootenay lakeshore does not reveal the calamity facing the Sinixt as their traditional way of life collapsed (above). An alien and small inhospitable Indian Reserve was set up for the Sinixt in 1902 on the Lower Arrow Lake but not many people chose to stay there. As a result, the Sinixt vanished from the West Kootenay along with their distinctive sturgeon nosed canoes (right). |

Sinixt and dog in sturgeon nosed canoe. |

|||||

Bryoria fremontii, also known as tree hair lichen. |

Like the Sinixt canoes, groves of ancient trees, 1000 years and older have vanished from the Inland Rainforest of the West Kootenay. To stop the unethical practice of old growth clearcut logging, the Slocan Valley has been mapped into Sinixt Cultural Zones. Ancient trees with unique lichen colonies are treasures of biological diversity and ecosystem continuity and have been the subject of scientific studies. Bryoria fremontii is an edible lichen, also used by the Sinixt as a traditional medicine mixed with grease and rubbed on the navels of newborn babies (left). Reference: Lichens of North America. Lichens in the Inland Rainforest are an essential food source for the woodland caribou, an animal traditionally hunted by the Sinixt. Today the species is on the edge of extinction, together with the ancient trees. |

|||||

Galena Bay on Upper Arrow Lake, Sinixt Territory. |

Galena Bay on the Upper Arrow Lake today appears a peaceful and serene place (left). A century ago, Sinixt people gathered at this ancient site each year in the early fall to fish and hunt while preparing their winter food stocks. This was an important site for the Sinixt, where they smoked fish in cedar huts and dried indigenous berries harvested from the surrounding forests. In 1894, the Sinixt discovered a shack built by a settler on their traditional camping place. A Sinixt be the name of Cultus Jim declared his aboriginal right to ownership but the settler claimed the white "squatter's right." During their argument, the settler shot Cultus Jim through his heart but was never charged for his cold blooded crime. During the dispossession of the Sinixt similar encounters must have been frequent, though few have been recorded. |

|||||

Silversmith mine, Sandon, Slocan Valley, c. 1900. |

The scarcity of habitable land in the Columbia, Slocan and Kootenay Lake valleys resulted in violent clashes between the immigrant settlers and the aboriginal inhabitants. No settler ever negotiated land rights with the Sinixt and many simply squatted on the land to claim the "white man's ownership" recognized by the government. The Slocan Valley remained isolated up until the discovery of silver deposits in 1891. Boomtowns such as Sandon (left) were established attracting thousands of newcomers eager to make a quick buck. These were wild and violent places where Sinixt people were not welcome. Around the mines, the land was razed in every direction, ancient forests were cut down and burned; and the waters were poisoned by mining wastes. |

|||||

See the virtual panoramas: Sandon and Kootenay Lake. In the 1890s, to serve the large number of settlers and miners moving into the West Kootenay, a transportation network of railways, roads and steamboat shipping routes was set up. The SS Rossland serviced the new mining and logging camps that were set up on Lower Arrow Lake (right). Edgewood Lumber Company, Castlegar, c. 1910. |

SS Rossland, Lower Arrow Lake, c. 1911. Hundreds of sawmills produced vast amounts of wood for construction and fuel for ore smelters. The Arrow and Kootenay Lakes were quickly deforested. When the Edgewood Lumber Co. (left) ran out of trees at its Lower Arrow Lake location, it moved down the Columbia River to Castlegar where continued to destroy the ancient forests. |

|||||

|

The deforestation of the West Kootenay was catastrophic. Within a century, entire forests had been ravaged by the logging industry, leaving the Sinixt without their traditional hunting and harvesting grounds on which they depended. "This was a Paradise. We had no hell, just a happy hunting ground. They made it hell for us ... When they landed here, they landed in heaven, and look what they did to it" Robert Watt, appointed Vallican caretaker of the Sinixt Nation. The western white pine (Pinus monticola) thrived in the Inland Rainforest of BC prior to the invasion by Europeans. The Sinixt word for the tree is "tl'i7álekw" which means "bark canoe wood." To cover the frame of a canoe, the Sinixt stripped the thin yet flexible bark off the heartwood of mature white pine in one sheet, a sustainable form of harvesting that left the tree living. Early loggers (right) felled the veteran white pines by hand using two-man cross cut saws and broadaxes. Later, power saws, diesel machinery and logging trucks facilitated massive clearcutting operations. Ancient white pines supplied industries such as the Powell Match Block Factory in Nelson from 1918 to 1960. Today these magnificent trees, so important to Sinxt culture, are gone from the landscape. |

Logger felling white pine near Chase, 1915. |

|||||

Cominco smelter on the Columbia River, Trail, c. 1934. To provide Cominco Ltd. with more power, the Waneta Dam was expanded in 2003. Today a new 435 MW hydro electric generator at Waneta is under review (right). The Waneta site is of cultural significance to the Sinixt: a village known as nkw'lila7 existed prior to the 1900s and a salmon fishery existed prior to the completion of the Grand Coulee Dam in c. 1940. Randy Bouchard and Dorothy Kennedy (2000). |

Whole valleys were denuded of trees to provide fuel for ore smelters. The Cominco smelter was built in 1896 on the site of a traditional Sinixt village, now the town of Trail (left). Today it is the world's largest zinc and lead smelting complex and dominates the town's viewscape from Cedar Avenue. During its first 100 years of operation, Cominco dumped c. 13.4 million tons of polluted slag including highly toxic concentrates of mercury and other heavy metals into the Columbia River.

Proposed Waneta expansion site, 2005. |

|||||

|

During the past century, no less than 15 major dams and generating stations have been built in the West Kootenay, including Bonnington Dam (1898); Revelstoke Dam (1910); Brilliant Dam (1944) and Waneta Dam (1954). These dams are part of the largest hydroelectric system in the world, centered on the Columbia Basin. In 1957, one year after the Sinixt had been declared extinct, Canada signed the Columbia River Treaty which provided the US with vast water and energy resources. New engineering projects in BC included the Mica, Duncan and Keenleyside dams. Hugh Keenleyside Dam inundated the Arrow Lakes in 1968. Out of a total of 152 archaeological sites recorded on the Arrow Lakes, only 12 remained above the high water level. The tragic result was that virtually all of the ancient Sinixt villages and burial sites, some of them thousands of years old, were obliterated forever. Brilliant Dam is currently expanding its powerplant (right). Built originally by Cominco and now owned by BC Hydro, this dam is located near the ancient Sinixt trading site and village of kp'ítl'els. |

Brilliant Dam, Sinixt Territory. |

|||||

Nemo Falls, Slocan Lake. |

Brilliant Dam is located on the Kootenay River, just upstream from its confluence with the Columbia River (above). This is the ancient Sinixt site of kp'ítl'els, where archaeological evidence dates about 5,000 years. kp'ítl'els was proposed as a reserve for the Sinixt in 1861, but instead it was pre empted by the BC government in 1912 and sold to Doukhobor settlers who renamed it "Brilliant" and deliberately plowed up and destroyed the sacred burial grounds of the Sinixt. Today there are few remaining natural cascades in the Kootenays, beautiful nature treasures such as Nemo Falls (left). In addition hydro electric dams have destroyed once thriving native fisheries. See: Center for Columbia River History. Oldtimers in the area remember trophy-sized sturgeon over 10 ft in length and up to 750 lbs in weight. One white sturgeon captured on the Kootenay River near the Brilliant Dam was 255 pounds. |

|||||

The failure of the BC government to establish a reserve at kp'itl'els resulted in the exile of many Sinixt people. By 1900, Baptiste Chistian and his family were among the few Sininxt survivors still living here. Time and time again Baptiste and his brother Alexander Christian (right) asserted their ancestral rights to kp'itl'els and expressed their deeply felt attachment to it. In 1911 his sister died at kp'itl'els, her suspected murderer was never brought to justice. In 1914, Alex Christian pleaded unsuccessfully to the Royal Commission on Indian Affairs to be allowed to remain at his home in kp'itl'els: "I wish to state that I was born there and have made that place my head quarters during my entire life. Also my ancestors have belonged to there as far back as I can trace. Both of my parents were born there and three of my grandparents. . . I want to stay in the home where I have always been and want that I have a piece of land made secure for me. . . I also ask that the graveyards of my people be fenced and preserved from desecration." In 1919 his wife, Teresa, died of pneumonia at kp'itl'els. After their land was taken, Alex and his daughter, Mary, age about five, travelled by canoe to Kettle Falls. In 1924 Alex Christian died in Omak of tuberculosis. Today his grandson, Lawney L. Reyes, is an author and artist living in Kirkland, Washington. |

Alex Christian, "Indian Alex," 1914. |

|||||

Totem pole and Credit Union, Edgewood, 2005. |

Log dump at Edgewood, Lower Arrow Lake. "Most of the Sinixt traditional villages and burial grounds were flooded with the damming of the Arrow Lakes. We know of only one monument to the Sinixt. In the town of Edgewood, there is a totem pole [left] that was erected in the late 1960's. It was commissioned by British Columbia Hydro as a commemorative to an extinct race. . . Totem poles were made by Haida natives and never the Sinixt. But beyond this fact is the reality that the Sinixt are not extinct" Sinixt Nation. |

|||||

No archaeological studies were done on the ancient village and burial sites of the Arrow Lakes prior to inundation in 1968. This heartland of Sinixt Territory included fisheries, hunting grounds, berry harvesting places, culturally modified trees and pictograph sites. In just 100 years, all has disappeared with settlement, mining, deforestation, road building and dam construction. Today annual cycling of water levels upturns archaeological artifacts such as arrowheads and knives, granite pounders, drift net weights, stone scrapers, crushers and drills. The site now occupied by the town of Edgewood was the location of a Sinixt trading centre and countless artifacts have been privately collected here: Inonoaklin Valley Virtual Museum. |

Arrowhead found near Edgewood. |

|||||

|

The brother-in-law of Alex Christian was Sinixt James Bernard, born c. 1850 (right). For over 30 years, he lived in the Kettle Falls area near Colville, where he was a chief. His poignant message to those who took so much from his family and from the Sinixt People: "It is for me to say that you white men, when you came here and landed, you came on a little piece of bark, and with a few sticks tied together, and a few of you on it. You found us that day in plenty; you had nothing. You did not bring your wealth with you." Chief Bernard died in 1935. During his lifetime, he witnessed the near extinction of his People as well as the environmental devastation of Sinixt Territory caused by the invasion of settlers: "Before the coming of the white man, our resources on this continent, if we could sum it up, had a value we could never put into figures and dollars. Our forests were full of wild game; our valleys covered with tall grass; we had camas, huckleberries and bitter root, and wild flowers of all kinds. When I walked out under the stars, the air was filled with the perfume of the wild flowers. In those days, the Indians were happy, and they danced day and night, enjoying the wealth created by the Almighty God for the Indian's use as long as he lived." |

Sinixt Chief James Bernard, c. 1930. |

|||||

|

||||||

|

Vallican | |||||

Source: www.firstnations.eu Printed:

Copyright: All Rights Reserved. Researched, written, compiled, formatted, hyperlinked and encoded by Dr. Karen Wonders. Images and intellectual property rights reside with the credited owner. Commercial transmission and/or reproduction requires written permission. Use for educational and research purposes requires proper citation.